Between March 2020 and March 2022, Stop AAPI Hate—a coalition that tracks and responds to incidents of hate, violence, harassment, and discrimination against Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders in the United States—documented more than 11,400 hate-motivated incidents against Asian Americans. Incidents include violence or death ranging from the mass shooting of eight individuals, six of them Korean women, at a spa in Atlanta in March 2021 to the death of a 40-year-old woman pushed in front of a subway car in New York City in January 2022. Horrific crimes have also occurred this year, including an 18-year-old Indiana University student who was stabbed multiple times in the head while riding a bus in Bloomington, Indiana, on January 15 and, most recently, a mass shooting on January 22 at a dance hall in Monterey Park, California, that killed 11 people and injured at least 10 others during a celebration of the Lunar New Year.

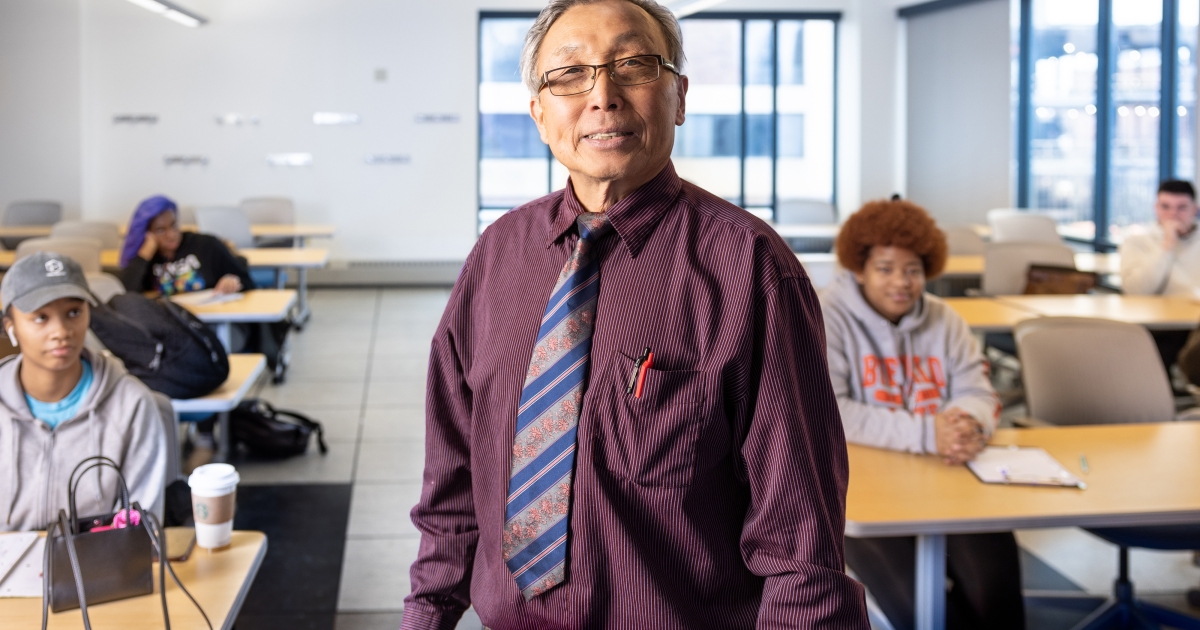

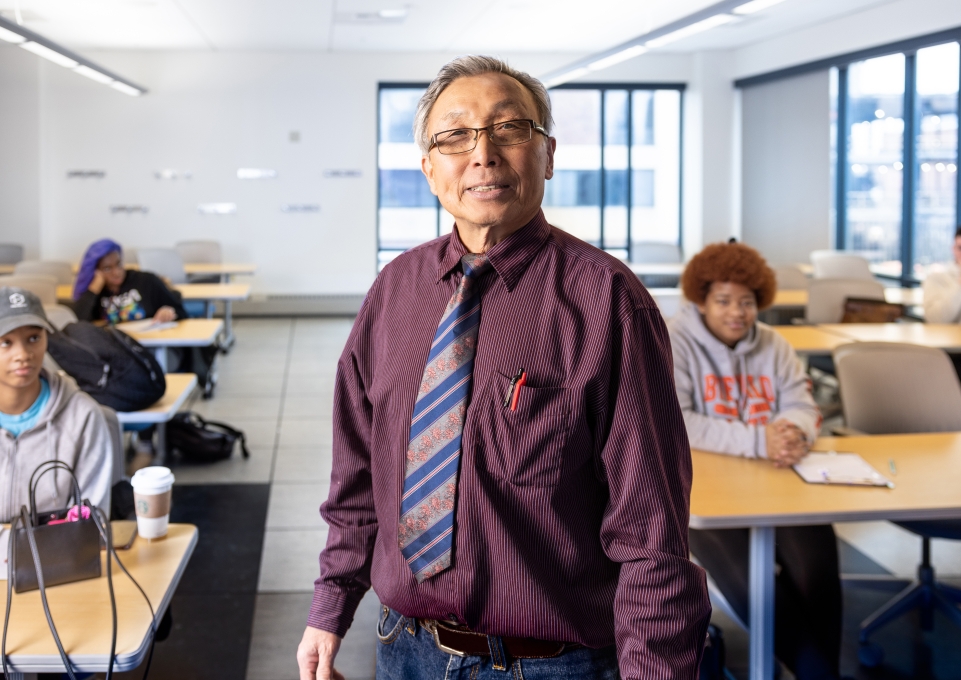

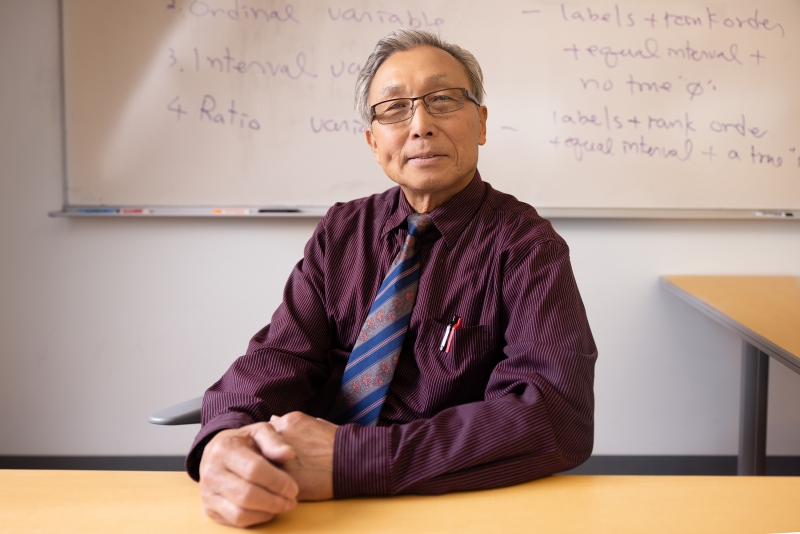

John Song, professor of criminal justice at Buffalo State University, weighed in on the recent surge of hate-charged violence, as well as the longer history of Asian American victimization.

Name: John Song

Title: Buffalo State University Professor of Criminal Justice

Song earned a Ph.D. in social ecology with a concentration in criminal justice from the University of California, Irvine; a master of arts in law enforcement administration from Western Illinois University; and a bachelor of arts in journalism from National Chengchi University in Taipei, Taiwan. His areas of specialization include Asian victimization and crime, comparative criminal justice, and social control.

When did you first study Asian American victimization?

When I was working on my Ph.D. at UC Irvine, almost 40 years ago, I focused on Chinese immigrants and Vietnamese refugees’ adaptation to the U.S. legal system. At that time, there was a rise in Asian-upon-Asian crimes and Asian gangs. They were primarily made up of young men who grew up during the Vietnam War who were here as refugees or whose families had immigrated from China. Their families were facing economic hardships, and they had some hostility about having to relocate to the States. These gangs thrived on the extortion of small-business owners in their Asian neighborhoods, along with home-invasion robberies, protection for gambling dens, and prostitution through massage parlors and hair salons. They were seldom selling drugs to survive. Gangs today have more options—drugs, human trafficking, cybercrime, and immigration fraud—and they are much less conspicuous fixtures of Chinese or Vietnamese enclaves.

What are some of the misperceptions about Asians living in America?

Asians are not a homogenous group, but most people don’t see that. I’m from Taiwan, for instance, which is very different from Mainland China or Malaysia or Vietnam.

When American society labeled Asians as the “model minority” in earlier decades due to Asian immigrants’ educational and financial successes, that might have inadvertently facilitated the rise of Asian hate crime by other minorities. There continues to be deep-seated jealously of Asian Americans and their perceived success.

Also, because of language and cultural barriers, Asian immigrants and refugees underreport their victimizations to police. This is part of the perceived vulnerability of Asians, and this doesn’t help them from being targeted.

Why did violence against Asian Americans escalate during the coronavirus pandemic?

We knew it was going to be a problem when the president of the United States and others publicly referred to COVID-19 as the “Chinese virus,” “Kong Flu,” and “Wuhan Virus.” People who were the most vulnerable were unjustly blamed for the pandemic.

You can see a kind of evolution of biased perceptions of Asian Americans and immigrants. It moves from ignorance to misconception to discrimination to jealousy to hate. What happened during the COVID-19 pandemic was like dousing oil on fire.

What other factors contribute to violence toward Asian Americans?

Today, the largest Asian immigrant group is Chinese. With the rise of China as a superpower, economically and otherwise, Chinese immigrants are coming to the U.S. much more financially prepared than previous generations. They’re able to purchase homes with cash in the suburbs of large cities in California, New York, Texas, and so on. Most of them drive luxury cars, wear designer clothes and jewelry, and live in the best school districts. Their children’s affluent appearance allows them to have affluent friends, mostly White, and their parents befriend the other kids’ parents. On one hand, Chinese immigrants feel comfortable here, but they are easily targeted by other politically and economically oppressed ethical groups.

In addition to prejudice and hate, sometimes the motive for the attacks is money; however, motivations are not always easily discerned when it comes to Asian hate crimes. I think mental illness often plays a role.

We also need to separate Asian hate incidents from Asian hate crime. Few Asian hate incidents get reported, but hate incidents sometimes give rise to hate crimes.

Photos by Jesse Steffan-Colucci, Buffalo State photographer.