It wasn’t until spring 2020—when the coronavirus pandemic changed life as we knew it in the United States and consumers suddenly faced empty shelves—that “supply chain disruptions” became part of the vernacular. While the economy has mostly rebounded and supply chain issues are improving, there are still hiccups and ongoing concerns. We spoke with Lorena Mathien, chair and associate professor of business at Buffalo State, about what goes into supply chain disruptions and what we can expect going forward

Name: Lorena Mathien

Title: Buffalo State Associate Professor and Chair of the Business Department

Mathien received a Ph.D. in operations management and strategy with a minor in management information systems from the State University of New York at Buffalo (UB) in 2012; a master of business administration (M.B.A.) from UB in 1996; and a bachelor of science (B.S.) in marketing management from Syracuse University in 1991. She joined the Buffalo State faculty in 2010 as the coordinator of professional applied and computational mathematics and also served as an assistant professor of mathematics. She has more than 20 years of industry experience, including working in supply chain management.

During the heart of the pandemic, what factors led to the dearth of goods?

Supply chain is very complex; it’s more of a mesh than a chain. What happened during COVID was a perfect storm created by three main things.

First, there was a shift in demand. For instance, when people started working from home, businesses weren’t buying toilet paper in bulk anymore while demand went up for the plush kind that consumers buy for their homes. Manufacturing can’t shift on a dime to meet a new demand. To add to that, people were panic purchasing—buying way more toilet paper and other household goods than they needed.

Second, when people weren’t allowed to work for a minimum of two months, it caused a labor shortage and an inventory shortage. You cannot replenish two months of inventory quickly. In addition, when people went back to work, they weren’t going back full time. Some companies are just now forcing employees back into the office. What we’re finding is that people may be productive at home, but they’re not productive at the same level. And even when factories were working at full capacity, there were not enough workers to unload the shipping containers and transport products from the West Coast by rail or truck.

Third were the structural factors—the way we organize our supply chains, the restrictions, and outsourcing. We have outsourced production through the years to focus on cost. These lean practices and outsourcing result in a loss of control when you have disruptions or shocks to the supply chain. Now, we’re seeing a big reversal in the outsourcing trend. There’s been a big increase in the manufacturing index over this past year in the United States, indicating that production is moving back to the States.

Where are the biggest supply chain problems currently?

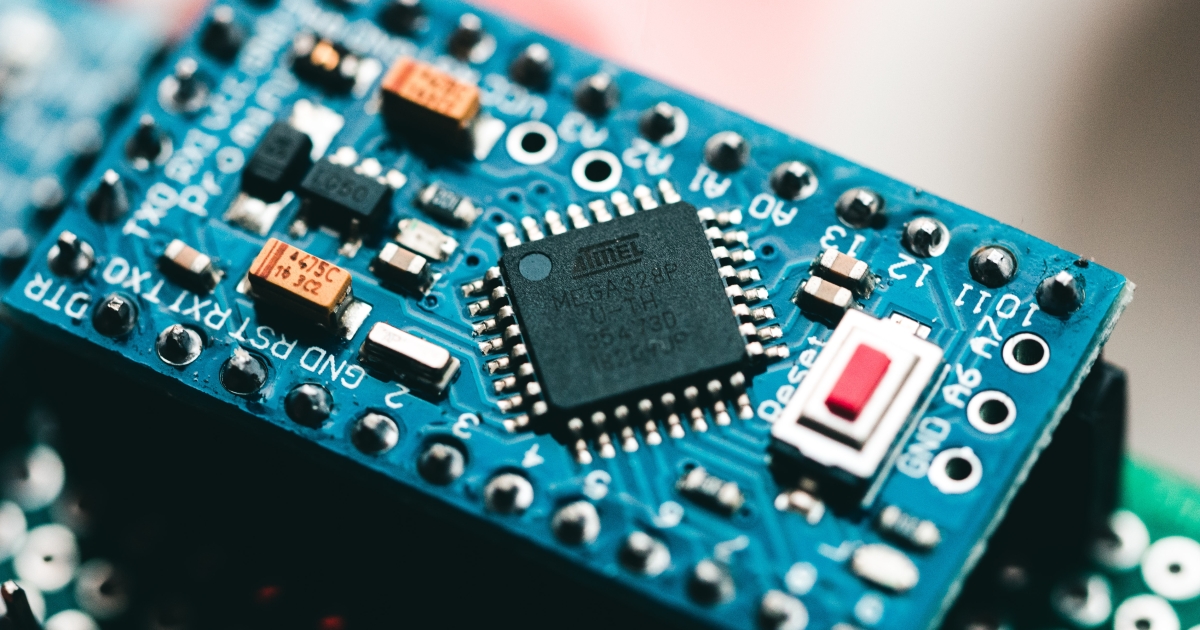

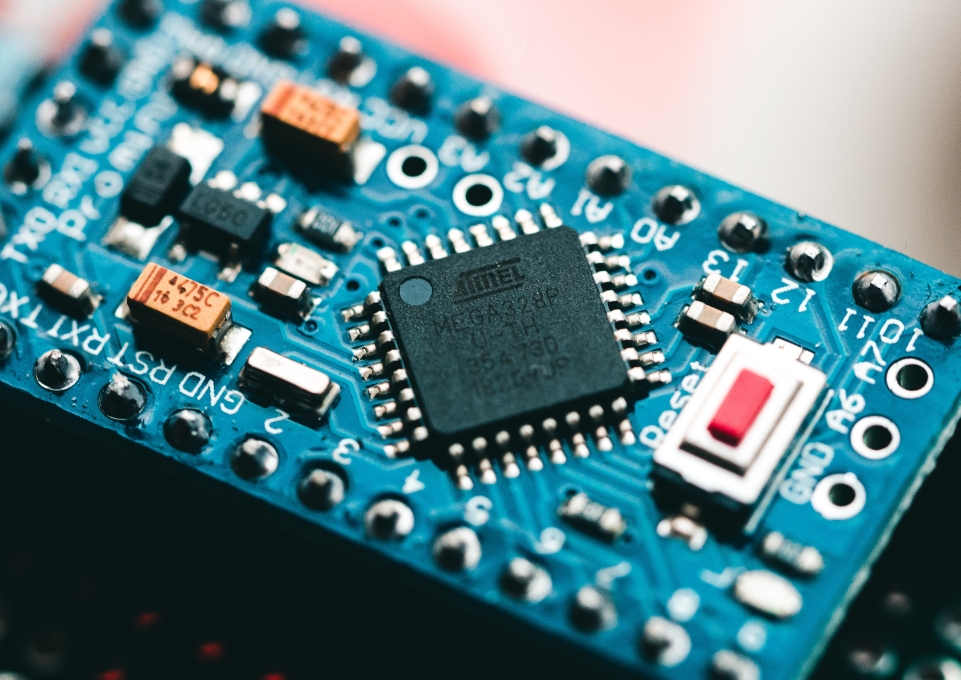

Because of a shortage of microchips, there’s a waiting list of about a year to get a new car. Before the pandemic, there was a decline in sales in the automotive industry resulting in manufacturers canceling orders of microchips from suppliers. Since these components are mostly outsourced to China and have a long lead time, the reverse of this automotive sales trend, combined with shutdown in China, has resulted in a shortage of chips, and thus a shortage of any products requiring these chips. We’re also still seeing a demand for construction and homes. Part of that started with the mass exodus from big cities during the pandemic. Sometimes people moved to areas where there wasn’t enough housing stock. That resulted in a huge increase in home prices. That’s starting to slow now with the rise of mortgage rates.

Labor shortages are still a problem. Right now, there’s actually too much inventory with most goods because there aren’t enough workers to move it. People don’t necessarily want the manual labor jobs anymore. No one wants to work in the service industry. A lot of people shifted to working in e-commerce, which boomed during the pandemic. Even as brick and mortar stores have reopened, e-commerce is still huge.

There are also pockets of stress, such as the war in Ukraine, restrictions on the European corridor, and restrictions on airspace. Metals come out of those regions, which affects all kinds of manufacturing. And, of course, it’s raising fuel prices. China is imposing new lockdowns as a strict reaction to COVID, and that is affecting productions of semiconductors once again.

How are businesses coping, and what do you predict for the future?

Some companies are starting to implement long-term strategies such as insourcing or near shoring rather than outsourcing their products. They’re finding suppliers closer to the United States or adding multiple suppliers to their network.

Also, the U.S. government plans to put billions of dollars into research for semiconductor production. The CHIPS and Science Act aims to support domestic semiconductor production, new high-tech jobs, and scientific research. While this is not a short-term resolution, the intention is to reduce our country’s reliance on foreign production.

We are seeing a trend toward an increase in automation, including virtual reality, which companies like Amazon are already using for training. In the education world, we have to find ways to support the increase in automation. We’ll need more workers with degrees in the trades who understand how to support all that automation.

As the supply chain starts to balance out, companies will need to lower prices to increase nondiscretionary spending, since the spending value of income is lower due to high inflation. We may or may not see this occur, so it is difficult to assess and forecast consumer demand and its impact on the supply chains over the next several years.

This isn’t the end of supply chain disruptions, however. The pandemic is sitting there spiraling. What matters is how we react to it.

Top photo by Harrison Broadbent.

Inset photo by Buffalo State Creative Services, Marketing and Communications Office.