This April marks the country’s 25th recognition of National Poetry Month. Through the years, it’s become the largest literary celebration in the world, with events available to schoolchildren, published and aspiring poets, and lovers of verse that focus on the integral role poetry plays in our culture and our lives.

Several faculty members in Buffalo State College’s English Department who write and teach poetry shared their thoughts about the power of poetry, especially following a year of isolation, fear, and the new, often unpleasant reality brought on by the coronavirus pandemic.

“Poetry provides a reminder of the existence of imagination and of our hard-wired capacity for empathy.”

Can poetry serve as a source of healing?

“Poetry provides private and public healing in the most simple and profound way,” said Ed Taylor, lecturer, novelist, and author of one poetry collection and three chapbooks. “That is by rendering connection. There’s the reminder that there is no ‘other’ or ‘them’; there’s only ‘us.’ Poetry provides a reminder of the existence of imagination and of our hard-wired capacity for empathy. Plug in whatever problem you want to name; at least partly, it can be ameliorated simply by being able to imagine and feel who and what is affected.”

Joey Nicoletti, lecturer, essayist, and author of five poetry collections, also pointed to how poetry engenders empathy.

“For me, one of the greatest marvels of poetry is that it uses language at its most efficient to connect with readers, with human beings,” Nicoletti said. “Which is to say that poems that are well-made arouse feelings of empathy within the reader. If there’s anything that the pandemic has taught me, it’s that we can never have too much empathy, especially in this moment when many are suffering beyond measure.”

“One can articulate great pain and trauma without necessarily expecting an answer. Poetry can make it more manageable, taking it out of the dark and giving it a kind of nobility.”

Peter Ramos, associate professor and author of two books of poetry, noted that poetry can be a source of healing for poets and readers alike.

“My friend, the late poet Allen Grossman, wrote about poetry being the discourse of last recourse, meaning it’s an avenue to make sense of the world when all other avenues, even prayer, have been exhausted,” Ramos said. “One can articulate great pain and trauma without necessarily expecting an answer. Poetry can make it more manageable, taking it out of the dark and giving it a kind of nobility.”

Kim Chinquee, associate professor, author of several collections of flash fiction, and editor of the campus literary magazine Elm Leaves Journal, said she agrees with the observation of one of her creative writing students: poetry brings people together. This is a phenomenon Chinquee sees in her own writing.

“If I observe something and put it in a poem, it might help someone else see things in a different way,” Chinquee said. “Poetry opens our eyes and heals us, both as writer and reader.”

Meanwhile, Jennifer Ryan-Bryant, professor, coordinator of the graduate English program, and author of Post-Jazz Poetics: A Social History, agreed that poetry can have therapeutic properties.

“At least since the 1950s, American and British poets have written in a fairly personal mode that often draws on their life experiences and attempts to come to terms with emotional complexities,” Ryan-Bryant said. “At the same time, poetry allows writers and readers to draw connections between their experiences and real-world conditions.”

“Poetry opens our eyes and heals us, both as writer and reader.”

Has poetry helped you or your students through the pandemic?

“I use poetry—and art—just to crawl to the finish line of regular days, which often have their own version of pandemics,” Taylor said. “I say that not to make light of a real pandemic, but just to use metaphor, which all of us do every day to make sense of the world. That is what poetry does.”

In March, Chinquee participated in a virtual reading with her longtime writing group, a mix of flash fiction writers and poets who are spread across the globe.

“It was really healing to be together in a way we wouldn’t have been without the pandemic,” Chinquee said. “During 2020, we committed to creating one piece of writing each day. That has helped me to get through this time of isolation.”

Last semester in Ramos’s Introduction to Creative Writing course, he asked students to freewrite for 15 minutes over Zoom.

“A lot of their writing was about trauma, not just COVID-related,” Ramos said, adding that a few students did address the lockdown and having to deal with themselves and their problems. “I think they realized it also provided opportunities to investigate and cultivate an interior life.”

Chinquee agreed that the forced isolation of much of the past year may have resulted in writers and poets noticing things they wouldn’t have before.

“Poetry allows writers and readers to draw connections between their experiences and real-world conditions.”

“It forces you to be quieter and more still,” she said. “If you’re isolated, your poetry may be more introspective.”

Nicoletti described poetry as an integral part of his daily life, akin to eating.

“I do something creative each day, and the pandemic has been no exception in this regard,” he said.

However, when the pandemic first hit and he could no longer interact with his colleagues and students, he said he felt despondent.

“I wrote down my feelings, just as a way of letting them out and as a sort of preventative measure to keep them from consuming me,” he said. He soon realized much of this writing was about baseball, which reminded him of the comfort the sport provided during a tumultuous childhood.

“I turned most of these writings into poems, which to my amazement, have blossomed into my next full-length poetry collection: Fan Mail,” he said. “It’s a collection of epistles: letters to baseball players from the past and present. As the poet Mark Strand posited, ‘We are at work on the past to make the future more bearable.’ Writing and teaching poetry has done just that for me, and uniquely so during the pandemic, which will also sustain me in the days to come.”

Additional thoughts about the benefits of poetry?

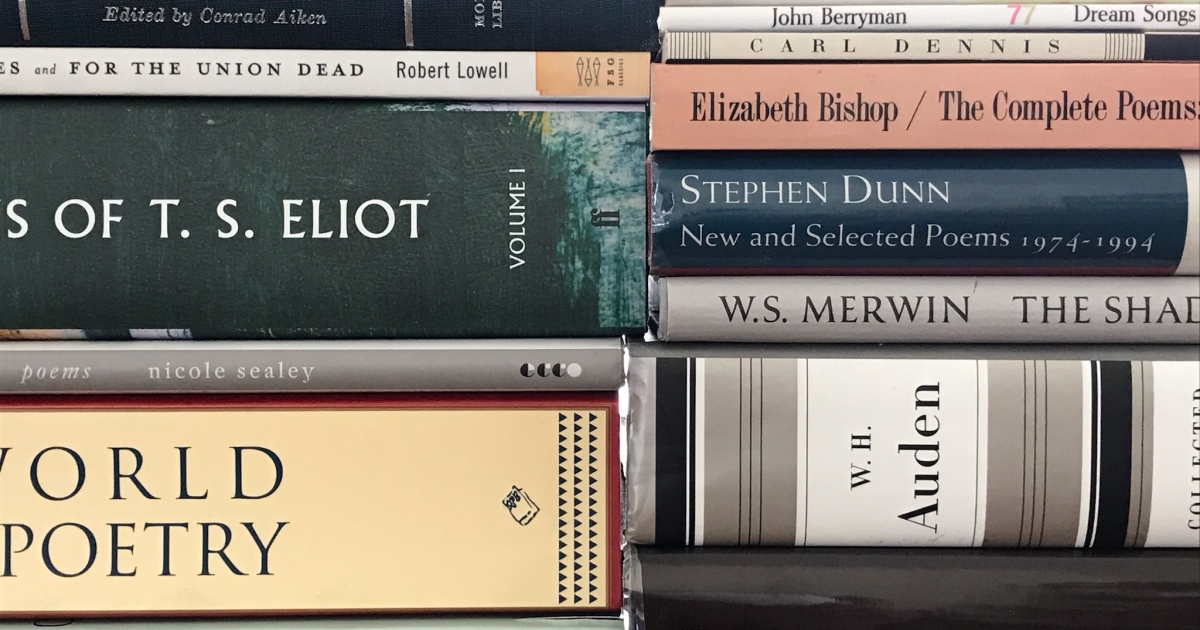

“To me, poetry is the most surgically precise use of language there is,” Taylor said. “It comes closest to rendering the complexities of sense, thought, emotion, and lived existence because it arises from a different place than regular expository language, as others have argued. As W. H. Auden said, poetry is ‘the clear expression of mixed feelings.’”

“Poetry infuses humanity with hope.”

Likewise, Ryan-Bryant said she loves reading, studying, and teaching poetry because of its ability to yield incredibly complicated and rich interpretation from a short, dense form.

“In doing that work of interpretation, and in sharing it with others, we learn about ourselves and what we can do to live better lives with others,” she said. “That is very true of every moment in human history, but poetry has taken on a new energy in connection with Black Lives Matter. Amanda Gorman’s performances at President Biden’s inauguration and at the Super Bowl testify to the importance of poetry as personal and social expression during the pandemic, along with other concurrent social movements.”

Nicoletti said, “Poetry infuses humanity with hope, like the best vaccines, which are becoming more available each day and benefit everyone, on and off the page, in personal space as well as cyberspace.”

Taylor summed it up this way: “To convey the complexity of experience and feelings—not just intellect and memory and rationality—it’s our best linguistic tool. I talk with students about poetry as information for daily living. It’s not written for classrooms; it’s written for life.”

Photo by Nancy Paschke.