When first-year students enter Buffalo State College, they have an opportunity to delve into big ideas and forge connections with their peers through Bengal Learning Communities.

First introduced to the campus in 2001, learning communities were reimagined in 2017, said Leasa Rochester-Mills, director of academic transition programs, including learning communities.

Open to all students, learning communities (LC) now consist of at least two connected courses in the fall with a cohort of 20 to 25 students. First-year students may choose a living-learning community, or ones based on academic interest areas or majors.

Benefits to both residential and commuter students are plentiful.

“We know that students engaged in learning communities have higher grade point averages and retention rates than their peers, report feeling more connected to the faculty and the college as a whole, and become more involved with the community,” Rochester-Mills said.

About 250 students are participating in 10 learning communities this academic year. They range from First Gen, which helps first-generation college students succeed, to Curious Minds, which provides students with a deeper understanding of mathematics, creativity, the arts, college life, and community.

In the Transforming Lives through Teaching LC, childhood education and special education and childhood education majors just completed the courses Individuals with Special Needs and School and Society together this fall.

“There are four interrelated principles of social justice we focus on in the two courses—equity, access, participation, and rights—that meet the required Diversity Intellectual Foundations [DIF] outcomes,” said Judi Harris, lecturer in special education who taught Individuals with Special Needs. “It’s a perfect pairing.”

Nyandusi Nyachae, lecturer in social and psychological foundations of education who taught School and Society, worked with Harris to oversee students’ examination of social justice for individuals with disabilities and those in urban environments.

“Nyandusi and I integrated several assignments based on the DIF outcomes,” Harris said. “One was the study of the book Black Appetite. White Food: Issues of Race, Voice, and Justice Within and Beyond the Classroom, by Jamila Lyiscott.”

To adjust to the pandemic-required restrictions this fall, Harris said, students successfully created and shared assignments over Blackboard Collaborate and developed read-aloud activities for children at Herman Badillo Bilingual Academy in Buffalo via YouTube.

The latter was a service-learning project in collaboration with the campus’s Anne Frank Project (AFP). Eve Everette, assistant director of AFP, helped Harris and the students develop the project that reached almost 700 participants, including prekindergartners through eighth-graders and their family members.

“It gave our students opportunities to learn and effective ways to read texts aloud to children,” Harris said. “At the end of the project, they were asked to recognize, understand, and incorporate the cultural perspectives of the children they worked with.”

Residential Component

Students who participate in living-learning communities get the added bonus of making connections in the comfort of their residence halls. They are assigned rooms on the same floor with their LC residential peers or ones based on special interests, Rochester-Mills explained. Their shared spaces also include a common lounge and kitchen.

In 2018–2019, the college had nine living-learning communities composed of 210 students, or 12 percent of the first-year class. The following year, participation grew to 14 percent of the first-year class.

Rochester-Mills envisioned increasing participation even more by designating all or part of first-year residence halls as living-learning communities. She was discussing this possibility with representatives of the Residence Life Office when COVID hit and the idea had to be shelved.

“It’s an idea I’d like to pursue in the future,” Rochester-Mills said.

Philip Badaszewski, assistant dean for residence life, agreed.

“I know how beneficial living-learning communities are for students,” Badaszewski said. “I think we definitely need to increase capacity in order to better support and retain our students.”

Other ideas Rochester-Mills has for continuing to improve learning communities include faculty members providing some programming within the residence halls and requiring resident assistants assigned to a learning community to have the same major as the students they’re overseeing.

Finally, she would like to help create learning communities for sophomores.

“Research shows that 70 percent of our students are retained between the freshman and sophomore years, but drop off after that,” she said. “I’d like to develop a sophomore-year program to help sophomores become more engaged with their majors, thus becoming committed toward graduation.”

Harris noted that her students formed bonds this past semester, even though they interacted remotely.

Those kinds of connections are one of the best parts of learning communities, said Rochester-Mills, who has seen long-lasting friendships flourish.

Students also become close with the faculty members who taught their LC courses.

“Often students go back to that faculty member later for advice,” she said. “He or she is often the first person on campus the student trusted, thus becoming a mentor to the student.”

Rochester-Mills added that learning communities help faculty members, too.

“Through the necessary collaborations with faculty outside of their own disciplines and departments, they gain a richer understanding of the college,” she said, “and how all the separate parts can work together.”

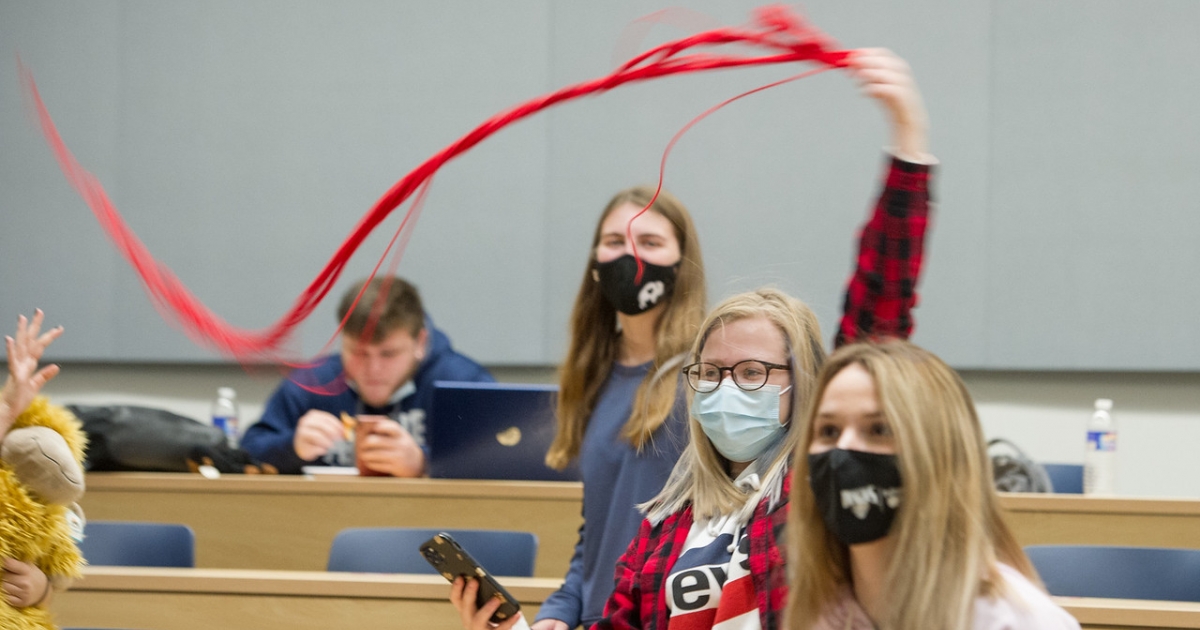

Photos by Bruce Fox, campus photographer.