A few years back, legendary English actors Sir Ian McKellen and Sir Patrick Stewart took to the streets of Manhattan on a warm autumn day. In town to headline revivals of No Man’s Land and Waiting for Godot, the two decided to add the role of tourist to their repertoires.

They strolled from landmark to landmark, chatting with fellow pedestrians and snapping photos along the way. Their journey eventually led to Christopher Park, a small wedge of Greenwich Village green space that is the site of Gay Liberation, the preeminent American monument to the gay liberation movement.

McKellen and Stewart sat on the monument’s bench, bookending the lacquered bronze figures of two women touching hands, and mugged for the camera. Stewart promptly tweeted the image to his 2 million followers with the simple message “Stonewall!”

Those seeing the tweet surely recognized the actors. But what about the sculpture? Who are those women? And what makes their story so important that it is forged in bronze for the ages?

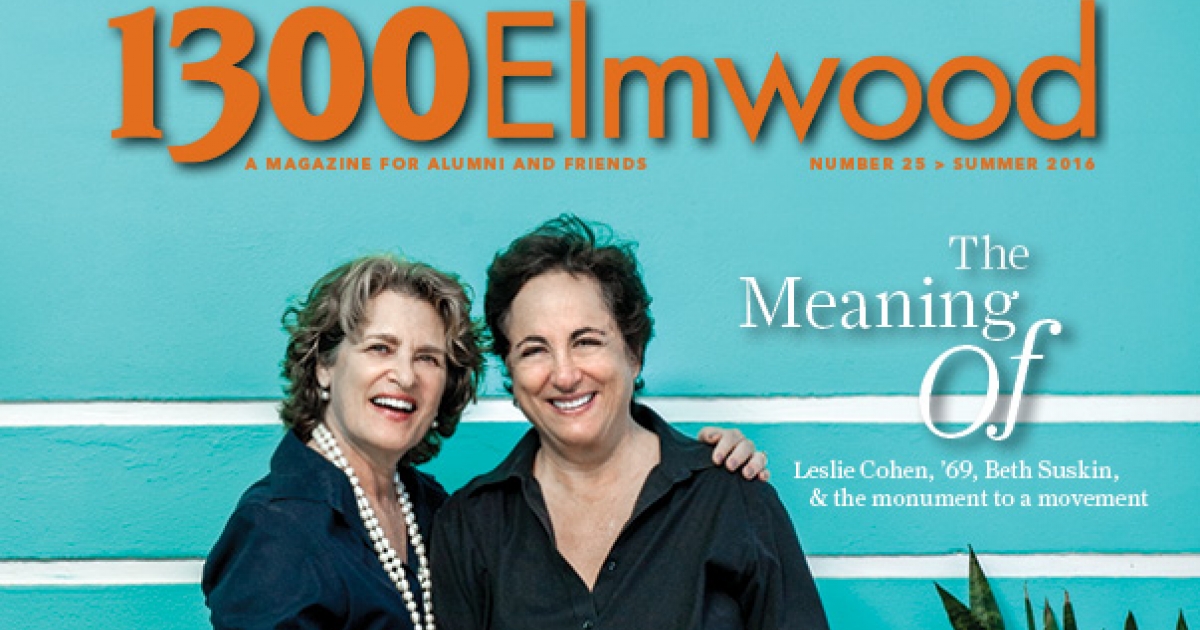

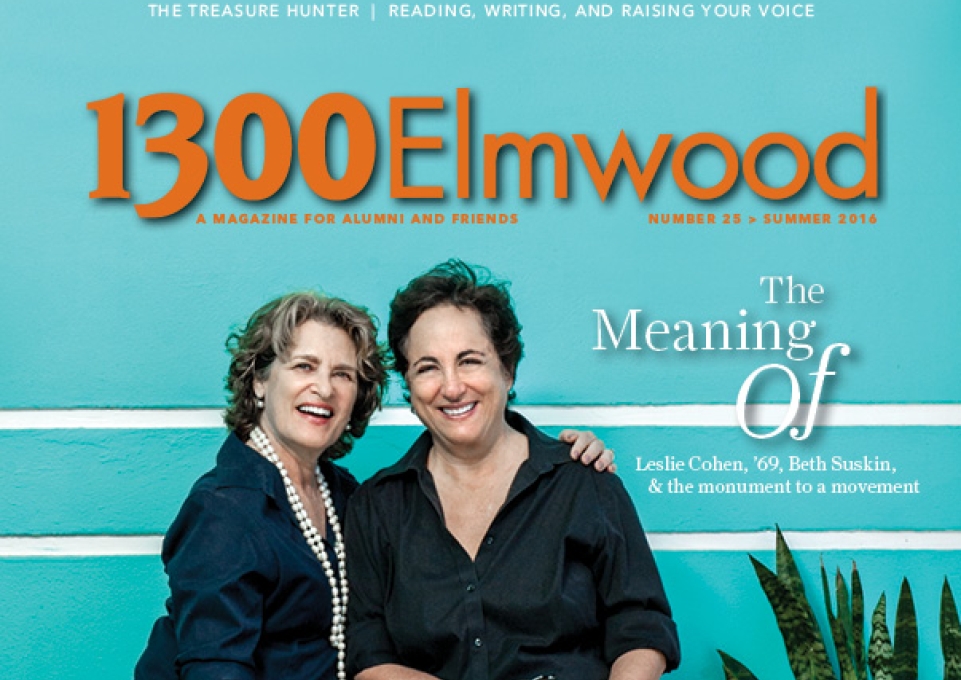

The answer: Leslie Cohen, ’69, and Beth Suskin modeled for the sculpture—and their story started right here at Buffalo State College.

Freshman Move-In Day, 1965

Leslie Cohen’s mother recognized the voice immediately. Not someone she knew personally, but someone she was very familiar with—a fellow Jewish mother.

“Where you from?” she asked, setting one foot inside a neighboring Bishop Hall dorm room, no invitation expected or required.

“Hewlett Harbor!” Beth Suskin’s mother looked up and replied.

“Oh, really? Did you just arrive?”

“Yes.”

“Is your daughter a freshman, too?”

“Yes.”

“Oh, maybe you two can be friends, Les,” Cohen’s mother said, turning to her mortified daughter.

That’s it. That’s how Leslie Cohen and Beth Suskin met. Just like so many freshmen who meet on their very first day on campus—at the mercy of their embarrassing but well-intentioned parents—and then stay connected for years, decades, a lifetime.

Bay Harbor Islands, Florida, Present Day

Fifty years after meeting as awkward teenagers, Cohen and Suskin are the least awkward couple imaginable. They radiate comfort, elegance, confidence, and joy—all the qualities that make up the ideal friendship and the ideal marriage.

They’re both retired now. They spend their days listening to music, going to art exhibits, and eating out with friends. They keep a chic, sophisticated home—or at least Suskin does.

Cohen admits that she’s no interior designer and even a bit of a clutter bug. They laugh together. They fight over the remote. Most of all, they love the moment. This very moment. Every moment they are together. They love the now. And they know that their now is the direct result of their wonderful, wild, heart-wrenching, rollercoaster past. They’re grateful for that every day. And they wouldn’t have it any other way.

College Days, 1965–1967

After the Move-In Day introduction, Cohen and Suskin did, in fact, become friends, just as Cohen’s mother had hoped. The two initially connected over music, sharing a love for R&B, Motown, and jazz.

“We listened to music constantly and danced in our rooms to Otis Redding, Sam and Dave, Smokey Robinson, and James Brown,” Cohen recalled.

Suskin was a talented singer—already a professional—who during her high school years had fronted a group called the Valiants that played at Long Island beach clubs and had even been invited to perform at New York City’s Peppermint Lounge, the hot spot known as the birthplace of the “Twist.” Unfortunately, it turned out the Valiants were too young to play in that venue.

But Suskin always found other venues. One of her favorites was the underground tunnel that used to connect various buildings at Buffalo State. The tunnel had great acoustics, and Suskin and Cohen would turn the deserted passageway into their own late night sound studio—Suskin on vocals, Cohen on bongo drums. Cohen remembers one epic evening when Suskin belted out “Summertime” from Porgy and Bess, and then, taken by the moment, they spray-painted “James Brown Lives” in large red letters across the tunnel wall. When they heard footsteps, they made a dash for it—laughing hysterically.

“Wild-eyed, pseudo-bad girls escaping the scene of the crime,” Cohen laughed again at the memory.

Cohen and Suskin had fun together freshman year, but not everything was rosy. They had arrived at college under very different circumstances, and they were still just teenagers.

Cohen chose Buffalo State to get away—far away—from her life in Queens and her parents’ vitriolic relationship. She reveled in her newfound freedom and loved the social interaction she found on campus. Suskin, on the other hand, had left her high school boyfriend behind to go to college. Despite the 400 miles between them, the boyfriend kept close tabs on Suskin, calling daily and incessantly, inquiring about budding friendships. Feeling as though she were under CIA surveillance, Suskin retreated from college social life. And her isolation led to depression.

“We didn’t speak over the summer break, and during the first semester of our sophomore year, I would occasionally see her in the halls, but we were like strangers,” Cohen said. “It was difficult because I missed her, and, even worse, I knew she missed me.”

The free-spirited Cohen flew to Italy the second semester of her sophomore year to participate in the college’s popular study-abroad program in Siena. When she returned, she learned that Suskin had officially transferred from Buffalo State to Hofstra University to be closer to her boyfriend.

New York City, 1969

Cohen graduated from Buffalo State in 1969, the year Neil Armstrong walked on the moon. The year they began the Vietnam War draft lottery. The year Ted Kennedy drove off the bridge near Chappaquiddick. The year “Broadway Joe” Namath called his Super Bowl win. The year of the Manson murders. The year Jimi Hendrix national-anthemed Woodstock. The year the Stonewall riots started the gay liberation movement in the United States.

Seriously, what didn’t happen in 1969?

Cohen decided to immerse herself in artistic chaos amid the societal chaos and enrolled at Queens College in New York City to pursue a master’s degree in art history, where she studied surrealism and Dadaism. She was intrigued by the present-day relevance of these 1920s art movements that had reacted to the atrocities of World War I by looking at life through a completely new lens. She also read books by Colette and Anaïs Nin, who wrote openly about their affairs with other women, and articles by Betty Friedan and Gloria Steinem, who wrote about women’s liberation and Sapphic love.

Her mind swam. She grew up in the 1950s, a time when every girl was expected to get married—to a man, it went without saying— have children, and live happily ever after as a housewife. The white picket fence of expectations. But that no longer seemed to be what she expected for herself. She didn’t fit that mold.

Meanwhile, Suskin had already started that expected life. After leaving Buffalo State, she married her boyfriend in 1967 when she was 19 years old. Although it worked at first, the marriage eventually buckled under the weight of her husband’s jealousy.

“His paranoia made me more mentally ill than I already was,” said Suskin, who stopped singing for 11 years because her husband couldn’t handle the attention she gained from being on stage. “I could have no eye contact with anybody, because if I did, he would accuse me of having an affair. I stayed in my bed for six years after we married. I had my beautiful standard poodle, Damien, with me all the time. He was my sole source of emotional connection.”

It was the most painful time of Suskin’s life. But things would change for Suskin—and for Cohen.

Opening of Sahara, 1976

After grad school, Cohen landed a dream job at Artforum magazine and later became curator of the New York Culture Center. There she worked with well-known artists, writers, culturati, and a lot of very, very rich people. She crossed paths with Salvador Dali, Jasper Johns, Roy Lichtenstein, and Andy Warhol. After work, she attended dinner parties with the likes of Norman Mailer and Doris Duke.

This public, glamorous art life contrasted with her private, not-so-glamorous gay life.

After her first intense, romantic relationship with another woman ended, Cohen mourned the loss for a year, but then realized that the hurt she felt confirmed what she knew to be true.

“I was free—liberated in a way that I had never experienced before,” she said. “I no longer felt shame about being a lesbian. Accepting my sexuality helped unleash me from society’s constraints of gender and role playing and both defined me and emboldened me.”

She began accompanying friends to gay bars, which had effectively been outlawed and, therefore, were operated in the shadows by the mafia. The mob ran the clubs without liquor licenses or a thought toward sanitation. Entering a gay bar in the ’60s was like entering a bar during the Prohibition era—back alleys, secret knocks, and the ever-looming threat of police raids.

Cohen and her friends soon tired of the scene. That was no way to live, they thought.

So they did what young, hip, college-educated people do—they stayed up late into the night and devised a plan and identified a funding source. The plan? Cohen, Michelle Florea, Linda Goldfarb, and Barbara Russo would open New York City’s first women’s club, showcasing women in art, politics, and music. It would be revolutionary. It would be stylish and upscale. “A club created by women for women,” read the opening invitation. And the funding source? Goldfarb said her father would finance the operation, no problem.

While it turned out that Mr. Goldfarb wasn’t keen on this particular investment opportunity, the four did open their revolutionary club—which they called Sahara, an oasis in the desert of conformity—in May 1976 at 1234 Second Avenue at East 65th Street, a highly visible location in Manhattan’s fashionable Upper East Side.

And what a club it was.

Sahara hosted big-name celebrities, up-and-coming entertainers, influential politicians, and thousands upon thousands of everyday women and men who swooned over the club’s Italian sectional couches, swaying palm trees, rain lights, pumping sound system, and world-class collection of wall-to-wall artwork, curated by Cohen.

Sahara owned Thursday nights, when the club replaced disco with live music and welcomed gay and straight patrons through the doors. Young rocker Pat Benatar regularly took the stage, and soon-to-be-rocker Patti Smith read her poetry. Sahara also dominated the sociopolitical scene. Saturday Night Live’s Gilda Radner and Jane Curtin held a political fundraiser at the club for Elaine Noble, the first openly gay candidate elected to a state legislature. Jane Fonda and Tom Hayden did the same for Noble. Friedan and Steinem stumped for Carol Bellamy at the club.

These events were promoted for more than just the club’s financial success.

“I wanted to increase our visibility, to educate the outside world that lesbians existed in all shapes and sizes, to extinguish the false notions and stereotypes so that we would not be so foreign to them,” Cohen said. “I thought that if men, especially, could see women for who they really were, minus the obfuscation of power and the sexual component fogging their view, they would have a whole new appreciation and respect for them as people, friends, and business associates.”

College Reunion (of Sorts), 1976

A few weeks before Sahara opened, Cohen received a phone call from Dottie Coyne, ’69, a friend from Buffalo State who worked in Manhattan’s garment district.

“You are not going to believe who’s here with me right now,” Coyne said. “Beth Suskin from Buffalo State! She came in for a job interview and I just hired her!”

Cohen nearly dropped the phone. Beth Suskin. Beth Suskin. Beth Suskin was back—and no longer married.

Suskin had finally reached her breaking point. One night a few years prior, in one of his fits of rage, her husband threw her to the floor and threatened her. Instinct told her two things: she was in danger and her marriage was over. The next morning, after her husband left for work, she packed a small suitcase, fled to her parents’ house, and filed for divorce.

A few days after the phone call, Cohen hosted a reunion at her fourth-story walk-up for Coyne; Adrienne Rubin, ’69; Ellen (Soloway) Fox, ’69; and Suskin, who all met as students at Buffalo State.

Cohen and Suskin talked for hours that night, catching up on 11 years apart. It was a wonderful, glorious second chance. They both knew it.

Suskin said she was living with another man now, but that she was no longer in love with him. She said she needed more from a relationship—she needed a soul connection. When Cohen told her that she was on the verge of opening a nightclub for women, Suskin asked about her sexuality.

“I did not find her questions inappropriate, and welcomed her openness about a subject that others felt was taboo,” Cohen said. “Like a lifetime compressed in the flash of a moment, I knew I loved her. For someone who had given up on any notion of finding, or even believing in, everlasting love, the thought that she could be that for me was quite remarkable.”

Cohen and Suskin eventually got together in 1977, after a whirlwind of circumstances, ancillary relationships, “should-we-or-shouldn’t-we?” head games, societal pressures, and back-and-forth, raw, vulnerable letters—or, as Cohen called it, the “maelstrom of love.”

On May 3, 1977, Suskin wrote to her mother:

The most beautiful aspect of living is owning one’s life. Doing what feels right—taking responsibility. We are individuals with different perceptions, needs and attitudes. To be a healthy person, is to be connected with these needs and perceptions, and hopefully be fulfilled.

We are in this game for ourselves. If not, the fulfillment and satisfaction will never come our way. I am not living my life for anybody or according to society’s dictates.

TO EACH HIS OWN….

My life is Beth Suskin and Leslie Cohen. I have finally met my match. I have fallen in love with a person who understands and adores me. It is quite an INCREDIBLE relationship. All my needs are fulfilled. There is no doubt that we are spiritually connected and have always been, even back more than 12 years ago, when we first met in Buffalo.

Les is real, alive, happy, intelligent, loving, sensual, artistic, and sensitive and loved by many.

Her soul is my soul—music to the nth degree, art, theater, nature—colors in our environment—everything. Her enthusiasm is my enthusiasm. There is never enough time. When we are walking through the streets, walking into stores, eating in restaurants, the constant remark is:

“You two look so happy.” We are. I am.

According to society, it’s unfortunate that she is a woman. But for my life, it’s the most fortunate thing that’s happened to me. I must do what is best for Beth. [Leslie] appreciates me and respects me the way no one ever has. It’s like being a young girl and having a sleep-over date, whispering under the covers with your best friend.

Everything will work out because I want it to.

Monument Unveiling Day, 1992

Sahara closed after four years, when the property’s owner—who had plans to develop the high-rise into high-rent apartments—stopped cashing the club’s rent checks and surreptitiously forced them out of their lease. The club’s partners didn’t have the financial means to fight the battle in court, but they did leave a powerful legacy as the owners of an establishment that changed many hearts and minds during a pivotal time in American history.

Which takes us back to Christopher Park and the Gay Liberation monument.

Two weeks before Sahara was padlocked, Cohen received a call from David Boyce, a friend from the art world. He said that George Segal, the nation’s most prominent figurative sculptor, who had just completed Abraham and Isaac, the Kent State memorial, had been commissioned again by the Mildred Andrews Fund to create a sculpture commemorating the Stonewall uprising of 1969, a series of protests that followed a police raid on the Stonewall Inn, a gay bar in Greenwich Village. The uprising is considered the flashpoint of the gay liberation movement in the United States. The Stonewall Inn was granted National Historic Landmark status in 2000.

Segal asked Boyce to identify two male and two female models for the sculpture. Boyce found the task more difficult than he thought—several men and women turned him down because they wanted to keep their sexual orientation private.

But then he thought of Cohen—strong-willed, proud, outspoken—and was delighted to learn that both she and her partner, Suskin, were equally ready for this historic assignment. Both were committed to the idea that it would be difficult for anyone to understand or empathize with same-sex couples if they never actually saw them in public. Both believed that visibility was the key to awareness and that it was their responsibility to show that their love was as real and as worthy of respect as the love that anyone else shared.

“We have always received incredible feedback about our relationship,” Suskin said. “Love is contagious. People see love and it’s hard to be aggressive or antagonistic.”

Although the sculpture was proposed in 1979 and received community and design approvals by 1982, public opposition and a planned renovation of the park delayed the sculpture’s installation for 13 years. New York City Mayor David Dinkins unveiled the monument in 1992, while Suskin serenaded him with a rendition of “My Funny Valentine.” Meanwhile, a second cast of the piece had already been installed on the Stanford University campus in 1981.

On June 24, 2016, President Barack Obama recognized the historical significance of the 7.7-acre Greenwich Village site by naming it Stonewall National Monument, the first gay rights site to be designated as a national monument and part of the National Park Service.

“We consider it such an incredible honor to have sat for this monument and to have our story be connected to the larger story,” Suskin said. “All these years later, we still can’t believe it. When we’re in New York City, we’ll sit across from the sculpture and just watch people interact with it. Kids climb all over it. Grown men and women cry in front of it. It’s very moving.”

During the 1980s and 1990s, Cohen worked as a nightclub promoter, then earned her law degree and went into private practice as an attorney. Suskin successfully returned to her singing career, highlighted by a three-month run in 1985, singing American standards backed by a full orchestra at the Mikado, a 1,000-seat nightclub in Tokyo, Japan. Later, she returned to school for a master’s degree and became a licensed clinical social worker and psychotherapist.

Cohen and Suskin married in October 2015 in Florida, thanks to a Supreme Court ruling, 50 years after meeting at Buffalo State and 39 years since becoming a couple.

The Meaning Of

So what’s the meaning of it all? What is the meaning of life?

The meaning is different for everyone, of course. Each person has his or her own definition of courage, principle, passion, liberty, success.

But what Suskin wrote to her mother is worth repeating: “The most beautiful aspect of living is owning one’s life. Doing what feels right—taking responsibility.”

For Leslie Cohen and Beth Suskin, the meaning of life is simple. The meaning of life is love.