While majoring in art education at Buffalo State, G. Peter Jemison, ’67, had the opportunity to study Renaissance art for a semester at the University of Siena in Italy. He noticed the autumn weather was similar to that of Western New York’s, and he mentioned this in a letter penned to an artist who had visited his painting class, one he greatly admired—Charles E. Burchfield.

“To my surprise, he responded,” Jemison said. “Burchfield said because Siena was roughly at the same latitude as Buffalo, it made sense that Siena’s fall was similar. That’s my memory of Charles Burchfield, an artist I have great admiration for. He was a genius, in my estimation.”

Now a collection of Jemison’s multimedia artwork is intertwined with that of the artist he met as a young man. The arresting exhibition, Shared Light: G Peter Jemison and Charles E. Burchfield, is on display at the Burchfield Penney Art Center through the end of December.

Jemison, who was awarded an honorary doctor of fine arts from Buffalo State in 2003, curated the exhibit with Nancy Weekly, head of collections at the Burchfield Penney and the world’s leading authority on Burchfield. The juxtaposition of the two men’s powerful and sometimes haunting depictions of fields, trees, birds, and skies clearly illustrates similarities in style and subject matter.

Jemison instructs a group of docents in training.

“Both artists demonstrate a deep concern for the viability of the land,” Weekly said, “by showing examples of how it has been desecrated as well as how it has retained its original energy.”

A member of the Heron Clan from the Cattaraugus Territory in the Seneca Nation, Jemison recently talked about his work to a group of new docents at the Burchfield Penney.

Jemison said he creates art that embodies orenda, defined as “the traditional Haudenosaunee belief that every living thing and every part of creation contains a spiritual force.”

Many of Jemison’s pieces speak to his heritage, such as the sketch Dried Geometry, which features a field of corn, beans, and squash. “These are the three sisters,” he said, “and sustained us in a mainly agricultural society.”

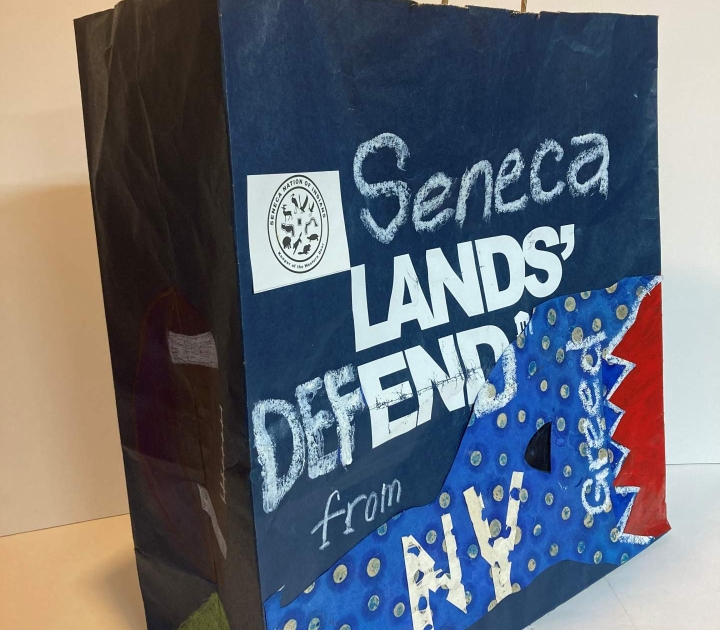

Others speak to the ongoing struggles of Indigenous people, such as a 2022 acrylic and oil pastel painting on a Lands’ End bag titled Defend Seneca Lands’ from New York Greed.

Jemison’s work Defend Seneca Lands’ from New York Greed.

Acrylic and oil pastel on Lands’ End bag, 21½ x 17½ x 7 inches

In a large, colorful painting titled At the Border, 2005, two identical black crows face one another across a barrier. Jemison explained that this painting symbolizes the separation of Indigenous people during the Revolutionary War, a conflict in which they were caught in the middle.

“It became a fight over who had a right to take our land,” Jemison said. “Many of the Haudenosaunee fled to Canada. The king offered them land along the border. Most stayed here. Later, a formal border was created between the two countries, though they looked the same.”

Jemison has two other crow paintings in the collection. In 1952, Burchfield created a lithography on paper featuring a crow in flight, titled Crows in March, which Weekly placed between two of Jemison’s crow paintings.

“It has been a pleasure to bring together works by two extraordinary artists for insight and contemplation,” Weekly said. “Their parallel visions reflect the symbolism, dynamism, and transcendent qualities of nature. Through their eyes, we can better appreciate our communal connection to the world. Visitors delight in the comparisons. Peter suggested the perfect exhibition title. Truly, their creativity emerged from Shared Light.”

Burchfield Penney hours and ticket information can be found on the museum’s website. The exhibition is on view through December 31. For more information, call (716) 878-6011.

Jemison’s painting At the Border, flanked by Burchfield’s lithograph Crows in March.

About G. Peter Jemison

G. Peter Jemison’s artwork has been shown internationally, and his writings have been widely published. He is active politically as an advocate for Native American rights. He was chairman of the Haudenosaunee standing committee on burial rules and regulations, fighting for the return of human remains and sacred objects from the antiques market to native peoples, which he said was possible because of the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act. He has been a spokesperson on related topics, and has participated in numerous symposia, including an early panel discussion held at the Burchfield Penney in the 1980s. Jemison was one of the founders of the Museum of the American Indian in New York City. His book, The Treaty of Canandaigua 1794, has been favorably received as an important contribution to history. In 2001, he was guest curator and wrote a catalog essay for The Pan-American Exposition Centennial: Images of the American Indian, held at the Burchfield Penney Art Center. The exhibition featured contemporary artists whose work explored identity, as opposed to how Indigenous people were misrepresented 100 years earlier. In 2021, K Art in Buffalo presented a survey of his work in the solo exhibition Orenda: Works by G. Peter Jemison with an accompanying illustrated catalog.

About Charles E. Burchfield

Watercolorist Charles Ephraim Burchfield (1893–1967) is one of America’s most original artists. Best known for his romantic, often fantastic depictions of nature, Burchfield developed a unique style of watercolor painting that reflected distinctly American subjects and his profound respect for nature. At the age of 50, he returned to ideas begun in early youthful fantasy scenes that he often expanded into transcendental landscapes. Burchfield, always probing the mysteries of nature to reveal his inner emotions, once stated, “An artist must paint not what he sees in nature, but what is there. To do so he must invent symbols, which, if properly used, make his work seem even more real than what is in front of him.” He followed this artistic vision until the end of his life, creating some of his most mystical works.

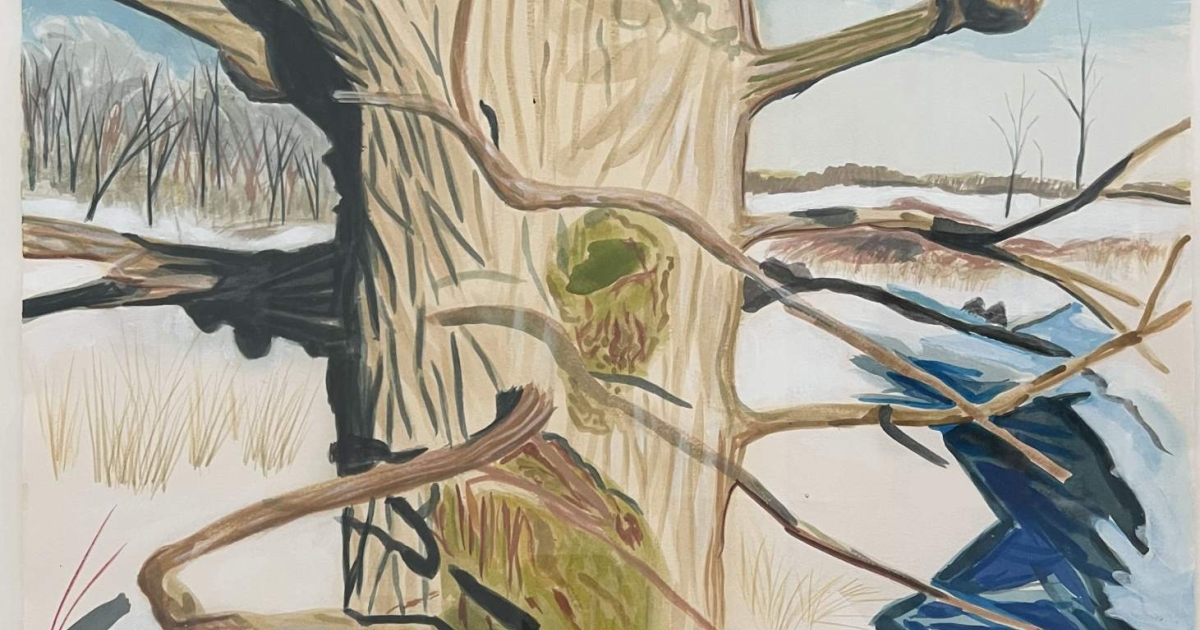

Top photo: G. Peter Jemison, Gnarled, 2002, acrylic on paper, 30 × 26 inches.