The early 1940s were a time of change, sacrifice, and perseverance at Buffalo State College, then known as the State Teachers College at Buffalo.

Heading out of the Great Depression, which decimated the country’s economic system throughout the 1930s, Buffalo State was in relatively good shape, thanks to financial backing at the state and federal levels.

But on December 7, 1941, Japan attacked the Pearl Harbor naval base on Oahu, Hawaii, widely recognized as one of the deadliest attacks on American soil by a foreign adversary. On December 8, 1941, President Franklin D. Roosevelt addressed the nation, delivering one of the most memorable lines in American history: “a date which will live in infamy.”

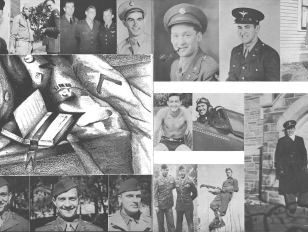

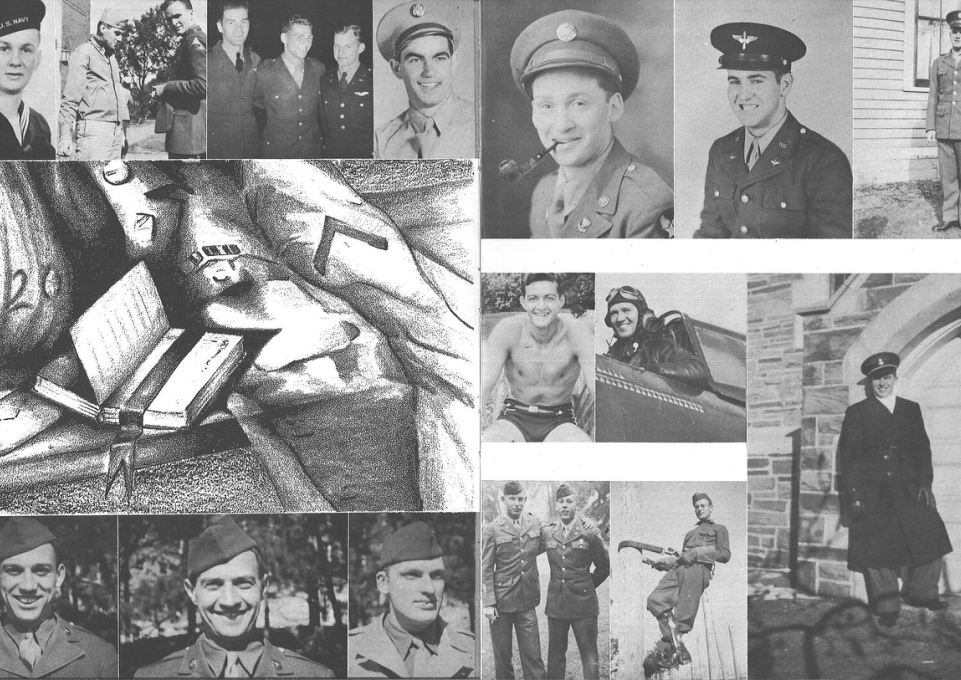

With America’s involvement in World War II came a significant drop in male enrollment in the college and changes to daily life on campus. Nearly 770 students and faculty members served during the war. Thirty died. And when the war ended in 1945, the rush of service members back to the States, buoyed by victory and the G.I. Bill, led to boom times for Buffalo State both in enrollment and campus construction.

With the onset of war, the number of male students enrolled at Buffalo State dropped almost immediately, from over 300 to less than 50, as men rushed to service.

Changes are apparent in the Record, the student-run newspaper, and the Elms yearbooks. Before Pearl Harbor, it wasn’t unusual to see a front-page story about the undefeated cross-country team, or a bus full of students traveling to a game in Syracuse. After that infamous date, however, the articles take on a more serious tone. In the January 16, 1942, issue, a piece headlined “Defenses Begun” lays out some of the steps being taken on campus to conduct air raid drills and collect materials needed for the war effort.

“Individual groups of the school have begun experimenting with air raid drills,” the article reads. “Two or three whole school drills will be tried soon.” The March 19, 1942, issue notes that the campus was ready for drills “after lots of preparation.”

Another article from the January 16 issue, titled “Call for Blood Defense May Mean Unit at State,” calls upon “normally healthy individuals from 17 and a half to 60” to help the armed forces by giving a pint of blood on campus.

Stanley Dietz, one of the first from Buffalo State to die in World War II.

The cover of the 1942 Elms shows a squadron of planes beneath the phrase “We Also Serve.” The Foreword begins and ends:

“There will never be another year like this past one, and there will never be another Elms like this present one…. Our energies, our resources, and our courage are now engaged in a war to prove that the free and democratic people of the world are, in the final test, the strongest people in the world.”

The 1943 Elms notes that “1942–43...brought to our campus more keenly the impact of the war through the curtailment of student activities.”

By 1944, the annual takes a more somber turn, calling the Class of 1944 a class divided “—divided by a war which has drafted most of its men from our campus. Like the tree for which it is named, the Elms has forked in two directions—the one depicting the life of service to college and community, the other, of much greater service to country. This is an Elms for you who will graduate in June...and for you who would have graduated had not fate intervened.”

It contains a special photo section, “They Serve,” including one of Stanley Dietz—“one of the first alumni from State to die in service”—showing the “soldier’s joy upon receiving mail from home.”

Throughout the war years, the Record is full of stories of the campus community’s war efforts: book drives, blood drives, and organizing committees to send care and holiday packages and letters to service members overseas.

Interestingly, there is a gap in issues between May 1942 and October 1943, presumably due to the war.

Women from Buffalo State who served during World War II were also recognized in the Record.

“We are always hearing about our boys in service,” chides the November 19, 1943, article “Women in Service.” “It is time that we realized that of the ‘587’ honored on our service flag, 40 are women from State.”

President Harry W. Rockwell, who served as principal, and then as the first president, of Buffalo State College from 1919 to 1951.

Several service members wrote letters from wherever they were stationed around the world back to Buffalo State, providing firsthand accounts of what the war was like. Walter Mordaunt, president of the freshman class of 1942, chimed in from Sicily in the January 21, 1944, issue of the Record.

“I have had many opportunities to indulge in my fondness for travel,” he wrote. “I was sent first to North Africa, then to Sicily.... For myself, everything was full of wonder. I walked through every town with the wide-eyed expression of the provincial first visiting New York.”

Faculty member Don Brossman wrote from Camp Crowder in Missouri in the same issue, while training and preparing to deploy.

“We really keep busy out here,” he wrote. “We are learning about infantry, drill, manual of arms, rifle workmanship. Ju-jitsu, scouting, gas mask drill. Though the work is strenuous, I find myself in better physical condition than many men younger than I am.”

Throughout the course of the war, Buffalo State President Harry W. Rockwell had an eye on the post-war campus. Anticipating an influx of students after the war’s end, the Post-War Planning Commission approved the construction of a new library, a new science building, and a new industrial arts building. The Exceptional Education Department was founded in 1944, and the master of science in education degree was approved in 1945.

With the war’s end on September 2, 1945, service members from various deployments around the world started to return home, and started to think about their next steps. For many, that included going to college.

The Servicemen’s Readjustment Act of 1944, also known as the G.I. Bill, afforded returning soldiers an opportunity to go to college they might not have had before the war. The G.I. Bill provided returning veterans with payments for tuition and living expenses to attend college or vocational school, as well as low-cost mortgages, low-interest loans, and a year of unemployment compensation.

A special issue of the Record on May 12, 1944, was dedicated to the 650 members of the campus community serving in the war, and included a rendering of what campus would look like as it expanded. The February 8, 1946, issue notes that the “second semester” was filled to capacity, largely from veterans returning home and enrolling in the Industrial Arts Department.

“These veterans are returning from every theatre of war and represent all branches,” the article says. “[Professor of vocational education Irving C. Perkins’s] reaction to this influx of students is that we are glad to have them with us again and that they are probably glad to be back.”

The Foreword to the 1945 Elms, however, hints at the disillusionment of the Beat Generation to come:

“Wrenched out of its one chance for a normal college life, the Class of 1945 has been thrust into a world of insecurity and introspection as to what it’s all about. We have questioned traditions as to their relative value in light of present world events, and have appraised their worthwhileness....”

It would be another generation before the Buffalo State community would again be torn asunder by the civil unrest of the Vietnam era. For now, the campus—elated by the twin victories of V-E and V-J days—was at peace.

(Sources for this story include New York State College for Teachers at Buffalo: A History 1871–1946, by Andrew W. Grabau, Charles A. Messner, Harry W. Rockwell, and Kate V. Wofford [1946]; the Record student newspaper, the Elms student yearbooks, and E. H. Butler Library Archives and Special Collections.)

Photos from top:

Tribute to WWII servicemen at Buffalo State College: 1944 Elms.

Stanley Dietz: 1944 Elms.

Harry Rockwell: President Harry W. Rockwell Digital Collection, E. H. Butler Library Archives and Special Collections.

Couples: 1945 Elms.

Troops of the 20th Armored Division and units of the 9th Army aboard the SS John Ericsson as it nears Pier 84, North River: World Telegram & Sun photo by Al Ravenna. New York, August 6, 1945. Library of Congress.

Explore Related Collections

Fronczak Room, Dr. Walter Drzewieniecki Collection

Walter M. Drzewieniecki (1914–2010) was a Buffalo State College history professor who started his career as a Polish military officer. He fought in the September 1939 campaign and then joined the Polish resistance movement. Later, he escaped Poland and joined the Polish Army in the Middle East, reaching the rank of captain during the invasion of Italy. He emigrated to the U.S. with his wife, Zofia, a lawyer who held leadership positions in the Polish YMCA attached to the Polish Army in Palestine and Egypt and then in Italy. She later became a librarian at Buffalo State College. The Fronczak Room Collection in Butler Library includes rich material on the Polish Armed Forces and YMCA during WWII; immigration to the U.S.; the Polish American community in the U.S.; Dr. Drzewieniecki’s Buffalo State College career, including the East European and Slavic studies and ethnic heritage studies programs that he headed; and the Drzewieniecki family.

World War II Prisoner of War Taped Interviews

World War II POW interviews conducted in 1990 by Mark Rieman as part of a master’s thesis in history. The collection includes eight interviews with veterans spanning one to two hours each and discusses their enlistment, boot camp, wartime experiences, capture, treatment, liberation, and reflections on their time serving in the military. To a person, they embodied the spirit of patriotism, honor, and commitment to preserving the freedoms of a country they loved.

These digital collections constitute a small portion of the materials available to researchers. For additional information, please contact E. H. Butler Library Archives and Special Collections.

Sidebar image: Polish infantrymen in September 1939 campaign. Drzewieniecki Collection, Fronczak Room